Men of broader intellect know that there is no sharp distinction betwixt the real and the unreal… — H.P. Lovecraft, The Tomb (1917)

La Belle Époque, a beautiful term for a Beautiful Age, as Light and Understanding replace Fear and Superstition, and Science and Art join hands in unholy matrimony and set out to discover the world anew. Trains become underground worms burrowing through the city, displacing medieval graves in the name of modernity; the Aéro-Club de France sends men into the heavens, amazing the public; Muybridge proves horses fly too and wins a bet; Edison floods the world with light; biologists discover germs and defy Death; botanists grow tropical plants in Parisian glass-houses and affront Nature with hot-house orchids; the phonograph and the cinema fold Time and Space for the masses. And for some reason bicycles become rather popular. The world was getting smaller every day and the discoveries were getting bigger every week. How very diverting it all was…

In the land of Sona-Nyl there is neither time nor space, neither suffering nor death. – H.P. Lovecraft, The White Ship (1920)

During the period we now call the fin de siècle, worlds collided. Ideas were being killed off as much as being born. And in a sort of Hegelian logic of thesis/antithesis/synthesis, the most interesting ones arose as the offspring of wildly different parents. In particular, the last gasp of Victorian spirituality infused cutting-edge science with a certain sense of old-school mysticism. Theosophy was all the rage; Huysmans dragged Satan into modern Paris; and eccentric poets and scholars met in the British Museum Reading Room under the aegis of the Golden Dawn for a cup of tea and a spot of demonology. As a result of all this, certain commonly-accepted scientific terms we use today came out of quite weird and wonderful ideas being developed at the turn of the century. Such is the case with space, which fascinated mathematicians, philosophers, and artists with its unfathomable possibilities.

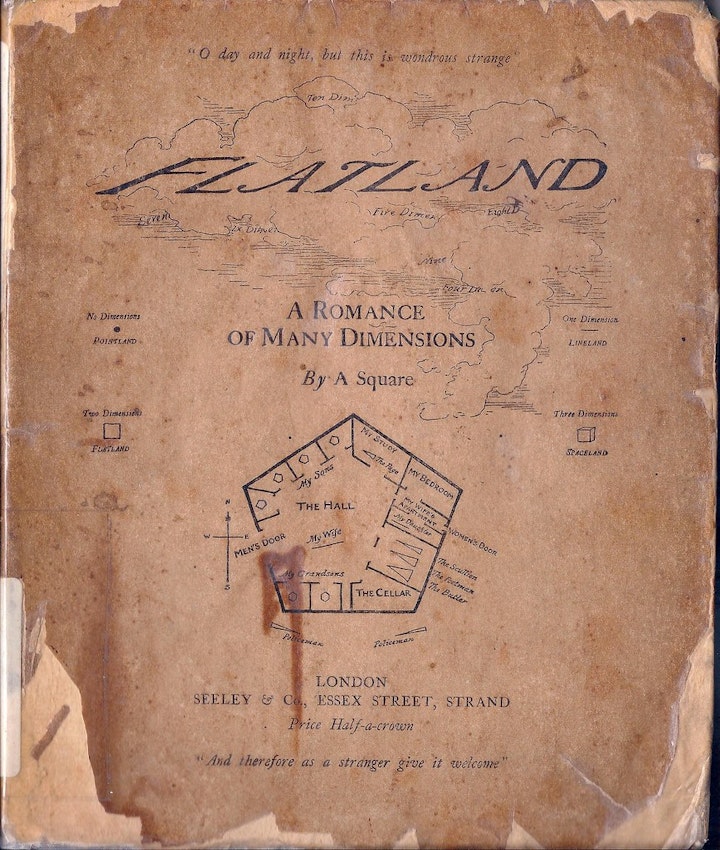

Outside of sheltered mathematical circles, the trend began rather innocuously in 1884, when Edwin A. Abbott published the satirical novella Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions under the pseudonym A. Square. In the fine tradition of English satire, he creates an alternative world as a sort of nonsense arena to lampoon the social structures of Victorian England. In this two-dimensional world, different classes are made up of different polygons, and the laws concerning sides and angles that maintain that hierarchy are pushed to absurd proportions. Initially, the work was only moderately popular, but it introduced thought experiments on how to visualise higher dimensions to the general public. It also paved the ground for a much more esoteric thinker who would have much more far-reaching effects with his own mystical brand of higher mathematics.

Cover of the first edition of Flatland (1884) – Source: City of London School Archive.

In April 1904, C. H. Hinton published The Fourth Dimension, a popular maths book based on concepts he had been developing since 1880 that sought to establish an additional spatial dimension to the three we know and love. This was not understood to be time as we’re so used to thinking of the fourth dimension nowadays; that idea came a bit later. Hinton was talking about an actual spatial dimension, a new geometry, physically existing, and even possible to see and experience; something that linked us all together and would result in a “New Era of Thought”. (Interestingly, that very same month in a hotel room in Cairo, Aleister Crowley talked to Egyptian Gods and proclaimed a “New Aeon” for mankind. For those of us who amuse ourselves by charting the subcultural backstreets of history, it seems as though a strange synchronicity briefly connected a mystic mathematician and a mathematical mystic — which is quite pleasing.)

Hinton begins his book by briefly relating the history of higher dimensions and non-Euclidean maths up to that point. Surprisingly, for a history of mathematicians, it’s actually quite entertaining. Here is one tale he tells of János Bolyai, a Hungarian mathematician who contributed important early work on non-Euclidean geometry before joining the army:

It is related of him that he was challenged by thirteen officers of his garrison, a thing not unlikely to happen considering how differently he thought from everyone else. He fought them all in succession – making it his only condition that he should be allowed to play on his violin for an interval between meeting each opponent. He disarmed or wounded all his antagonists. It can be easily imagined that a temperament such as his was not one congenial to his military superiors. He was retired in 1833.

Janos Bolyai: Appendix. Shelfmark: 545.091. Table of Figures – Source.

Mathematicians have definitely lost their flair. The notion of duelling with violinist mathematicians may seem absurd, but there was a growing unease about the apparently arbitrary nature of “reality” in light of new scientific discoveries. The discoverers appeared renegades. As the nineteenth century progressed, the world was robbed of more and more divine power and started looking worryingly like a ship adrift without its captain. Science at the frontiers threatened certain strongly-held assumptions about the universe. The puzzle of non-Euclidian geometry was even enough of a contemporary issue to appear in Dostoevsky’s Brothers Karamazov when Ivan discusses the ineffability of God:

But you must note this: if God exists and if He really did create the world, then, as we all know, He created it according to the geometry of Euclid and the human mind with the conception of only three dimensions in space. Yet there have been and still are geometricians and philosophers, and even some of the most distinguished, who doubt whether the whole universe, or to speak more widely, the whole of being, was only created in Euclid’s geometry; they even dare to dream that two parallel lines, which according to Euclid can never meet on earth, may meet somewhere in infinity… I have a Euclidian earthly mind, and how could I solve problems that are not of this world?

— Dostoevsky, Brothers Karamzov (1880), Part II, Book V, Chapter 3.

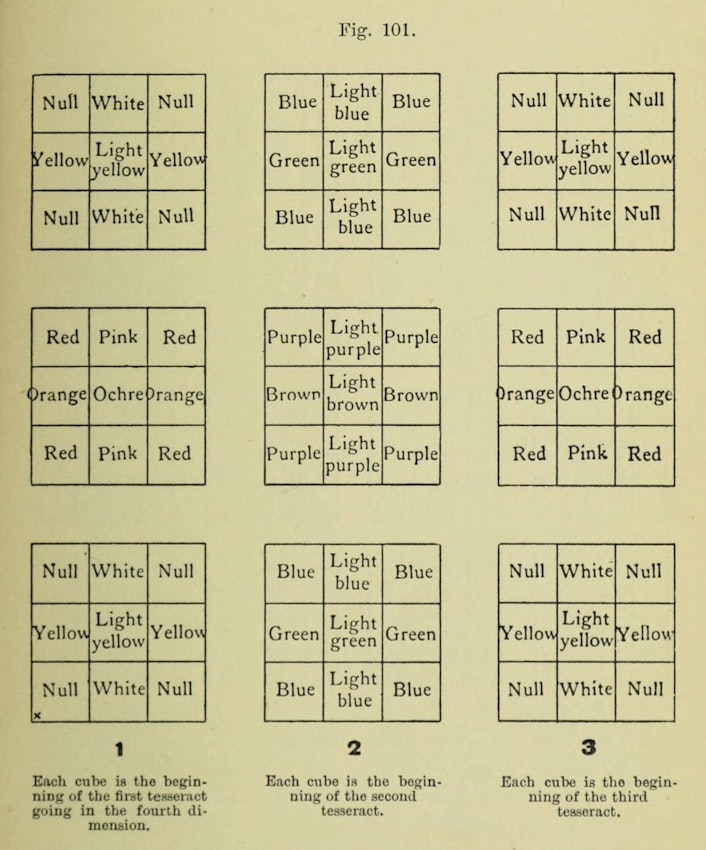

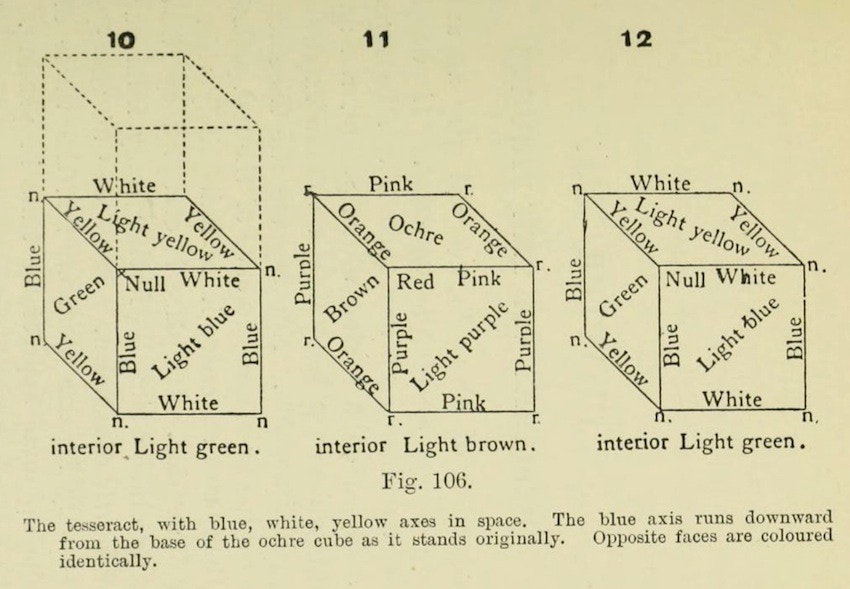

Well Ivan, to quote Hinton, “it is indeed strange, the manner in which we must begin to think about the higher world”. Hinton’s solution was a series of coloured cubes that, when mentally assembled in sequence, could be used to visualise a hypercube in the fourth dimension of hyperspace. He provides illustrations and gives instructions on how to make these cubes and uses the word “tesseract” to describe the four-dimensional object.

Diagram from Hinton’s The Fourth Dimension (1904) – Source.

The term “tesseract”, still used today, might be Hinton’s most obvious legacy, but the genesis of the word is slightly cloudy. He first used it in an 1888 book called A New Era of Thought and initially used the spelling tessaract. In Greek, “τεσσάρα”, meaning “four”, transliterates to “tessara” more accurately than “tessera”, and -act likely comes from “ακτίνες” meaning “rays”; so Hinton’s use suggests the four rays from each vertex exhibited in a hypercube and neatly encodes the idea “four” into his four-dimensional polytope. However, in Latin, “tessera” can also mean “cube”, which is a plausible starting point for the new word. As is sometimes the case, there seems to be some confusion over the Greek or Latin etymology, and we’ve ended up with a bastardization. To confuse matters further, by 1904 Hinton was mostly using “tesseract” — I say mostly because the copies of his books I’ve seen aren’t entirely consistent with the spelling, in all likelihood due to a mere oversight in the proof-reading. Regardless, the later spelling won acceptance while the early version died with its first appearance.

Diagram from Hinton’s The Fourth Dimension (1904) – Source.

Hinton also promises that when the visualisation is achieved, his cubes can unlock hidden potential. “When the faculty is acquired — or rather when it is brought into consciousness for it exists in everyone in imperfect form — a new horizon opens. The mind acquires a development of power”. It is clear from Hinton’s writing that he saw the fourth dimension as both physically and psychically real, and that it could explain such phenomena as ghosts, ESP, and synchronicities. In an indication of the spatial and mystical significance he afforded it, Hinton suggested that the soul was “a four-dimensional organism, which expresses its higher physical being in the symmetry of the body, and gives the aims and motives of human existence”. Letters submitted to mathematical journals of the time indicate more than one person achieved a disastrous success and found the process of visualising the fourth dimension profoundly disturbing or dangerously addictive. It was rumoured that some particularly ardent adherents of the cubes had even gone mad.

He had said that the geometry of the dream-place he saw was abnormal, non-Euclidian, and loathsomely redolent of spheres and dimensions apart from ours.

— H. P. Lovecraft, The Call of Cthulhu (1928)

Hinton’s ideas gradually pervaded the cultural milieu over the next thirty years or so — prominently filtering down to the Cubists and Duchamp. The arts were affected by two distinct interpretations of higher dimensionality: on the one hand, the idea as a spatial, geometric concept is readily apparent in early Cubism’s attempts to visualise all sides of an object at once, while on the other hand, it becomes a kind of all-encompassing mystical codeword used to justify avant-garde experimentation. “This painting doesn’t make sense? Ah, well, it does in the fourth dimension…” It becomes part of a language for artists exploring new ideas and new spaces. Guillaume Apollinaire was amongst the first to write about the fourth dimension in the arts with his essay Les peintres cubistes in 1913, which veers from one interpretation to another over the course of two paragraphs and stands as one of the best early statements on the phenomenon:

Until now, the three dimensions of Euclid’s geometry were sufficient to the restiveness felt by great artists yearning for the infinite. The new painters do not propose, any more than did their predecessors, to be geometers. But it may be said that geometry is to the plastic arts what grammar is to the art of the writer. Today, scientists no longer limit themselves to the three dimensions of Euclid. The painters have been led quite naturally, one might say by intuition, to preoccupy themselves with the new possibilities of spatial measurement which, in the language of the modern studios, are designated by the term: the fourth dimension. […]

Wishing to attain the proportions of the ideal, to be no longer limited to the human, the young painters offer us works which are more cerebral than sensual. They discard more and more the old art of optical illusion and local proportion, in order to express the grandeur of metaphysical forms. This is why contemporary art, even if it does not directly stem from specific religious beliefs, none the less possesses some of the characteristics of great, that is to say religious art.

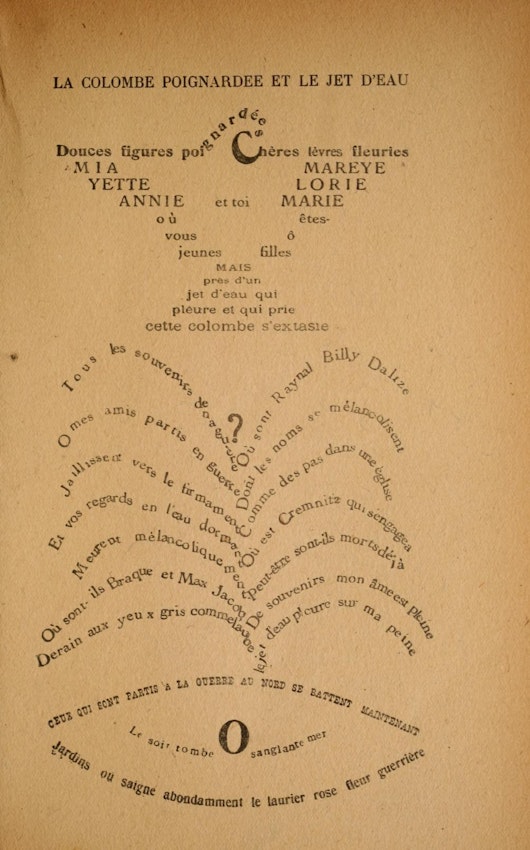

Whilst most suited to the visual arts, the fourth dimension also made inroads into literature, with Apollinaire and his calligrammes arguably a manifestation. Gertrude Stein with her strikingly visual, mentally disorienting poetry was also accused of writing under its influence, something she refuted in an interview with the Atlantic Monthly in 1935: “Somebody has said that I myself am striving for a fourth dimension in literature. I am striving for nothing of the sort and I am not striving at all but only gradually growing and becoming steadily more aware of the way things can be felt and known in words.” If nothing else, the refutation at least indicates the idea’s long-lasting presence in artistic circles.

A page from Apollinaire’s Calligrammes; poèmes de la paix et de la guerre, 1913-1916 (1918) – Source.

Some critics have since tried to back-date higher dimensions in literature to Lewis Carroll and Through the Looking-Glass, although he was, by all accounts, a fairly conservative mathematician who once wrote an article critical of current academic interest in the subject entitled “Euclid and his Modern Rivals” (1873). As a side note, Hinton once invented a game of three-dimensional chess and opined that none of his students could understand it, so perhaps Carroll would have appreciated that.

If anything, the connection between Carroll and hyperspace was the other way round, and the symbolic language employed by Carroll — mirrors, changing proportions, nonsense, topsy-turvy inversions and so on — was picked up by later artists and writers to help prop up their own conceptions of the fourth dimension, which, as we can see, were starting to become a bit of a free for all. Marcel Duchamp, for instance, coined the rather wonderful phrase “Mirrorical return” in a note about the fourth dimension and the Large Glass.

Illustration by Peter Newell from a 1902 edition of Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There – Source.

In the same period that Hinton’s ideas of the fourth dimension were gaining currency among the intellectuals of Europe our “secret sense, our sixth sense” was identified by neurophysiologist Charles Sherrington in 1906. Proprioception, as he called it, is our ability to locate where a body part is when our eyes are closed — in other words, our ability to perceive ourselves in space. And yet the sixth sense means something completely different to us nowadays, associated with another fin-de-siècle obsession: mediumship, the ability to perceive things in the same space but in different dimensions. It is worth noting that in those days, scientists – real, respected, working scientists — apparently looked towards spiritualist mediums for experimental evidence. At the same time, Hinton’s cubes were used in séances as a method of glimpsing the fourth dimension (and hopefully a departed soul or two). Hinton himself published one of his very first articles on the fourth dimension with the sensational subtitle “Ghosts Explained”. In defence of the era’s more eccentric ideas, though, so much was explained or invented in so very few years, that it must have seemed only a matter of time before life’s greatest mysteries were finally solved. In any case, the craze over a mystical fourth dimension began to fade while the sensible sixth sense of proprioception just never really caught on.

A spirit photograph by William Hope, ca. 1920 – Source.

But are not the dreams of poets and the tales of travellers notoriously false?

– H.P. Lovecraft, “The Street” (1919)

By the late 1920s, Einsteinian Space-Time had more or less replaced the spatial fourth dimension in the minds of the public. It was a cold yet elegant concept that ruthlessly killed off the more romantic idea of strange dimensions and impossible directions. What had once been the playground of spiritualists and artists was all too convincingly explained. As hard science continued to rise in the early decades of the twentieth century, the fin-de-siècle’s more outré ideas continued to decline. Only the Surrealists continued to make reference to it, as an act of rebellion and vindication of the absurd. The idea of a real higher dimension linking us together as One sounded all a bit too dreamy, a bit too old-fashioned for a new century that was picking up speed, especially when such vague and multifarious explanations were trumped by the special theory of relativity. Hinton was as much hyperspace philosopher as scientist and hoped humanity would create a more peaceful and selfless society if only we recognised the unifying implications of the fourth dimension. Instead, the idea was banished to the realms of New Age con-artists, reappearing these days updated and repackaged as the fifth dimension. Its shadow side, however, proved hopelessly alluring to fantasy writers who have seen beyond the veil, and bring back visions of horror from an eldritch land outside of time and space that will haunt our nightmares with its terrible geometry, where tentacles and abominations truly horrible sleep beneath the Pacific Ocean waiting to bring darkness to our world… But still we muddle on through.

What do we know… of the world and the universe about us? Our means of receiving impressions are absurdly few, and our notions of surrounding objects infinitely narrow. We see things only as we are constructed to see them and can gain no idea of their absolute nature. With five feeble senses we pretend to comprehend the boundlessly complex cosmos.

— H.P. Lovecraft, From Beyond (1920)

Jon Crabb is a writer and editor with interests in the fin-de-siècle, forgotten culture, the esoteric and anything generally weird and wonderful. He lives in London and works as Editor for British Library Publishing. He also runs their twitter feed, which he would like you to check out now.