James Tilly Matthews and the Air Loom

In 1810 John Haslam, a London apothecary, published the first ever book-length description of a mad person’s delusions. Until this point most medical case histories of what we now refer to as mental illness had amounted to a line or two at most, and more often just a single word such as “frenzied” or “melancholy”. But the opinions of James Tilly Matthews resisted any such summary. He described a previously unimagined world of futuristic machines, “magnetic spies” and mass brainwashing, woven into a bizarre but undeniably well-informed narrative of the high politics behind the Napoleonic Wars.

Haslam titled his book Illustrations of Madness, and it was full of lessons for the nascent profession of “mad-doctoring”, later to be known as psychiatry. But it was also written to settle a personal score. Haslam was the apothecary at the Royal Bethlem Hospital – in popular slang, Bedlam – where James Tilly Matthews had for the previous decade been confined as an incurable lunatic. Not everyone, however, believed that Matthews was mad. Haslam’s diagnosis had been contested by other doctors, and the governors of Bethlem had distanced themselves from it. He wrote his book in retaliation against his superiors; but as it turned out, his patient would have the last word.

Although Haslam has been relegated to a footnote in the history of psychiatry, his account of Matthews’ inner world is still cited as the first fully described case of what we now call paranoid schizophrenia, and in particular of an “influencing machine”: the belief, or delusion, that a covertly operated device is acting at a distance to control the subject’s mind and body. For everyone who has since had messages beamed at them by the CIA, MI5, Masonic lodges or UFOs, via dental fillings, mysterious implants, TV sets or surveillance satellites, James Tilly Matthews is patient zero.

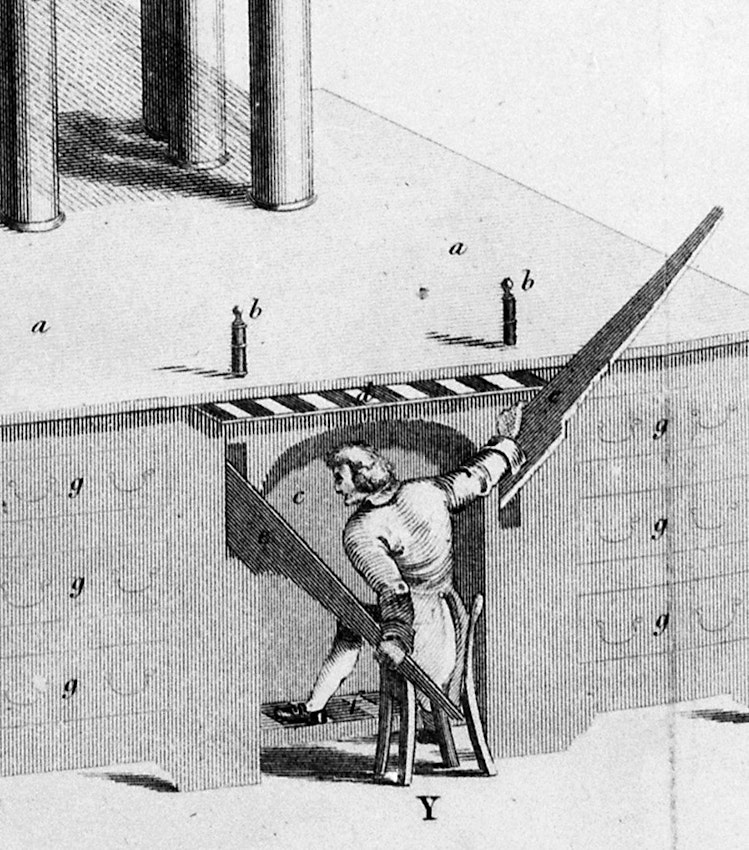

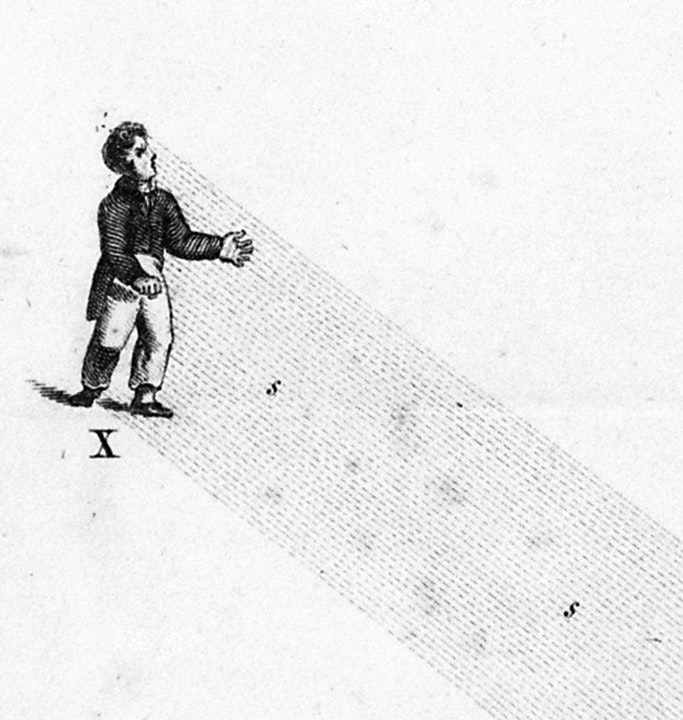

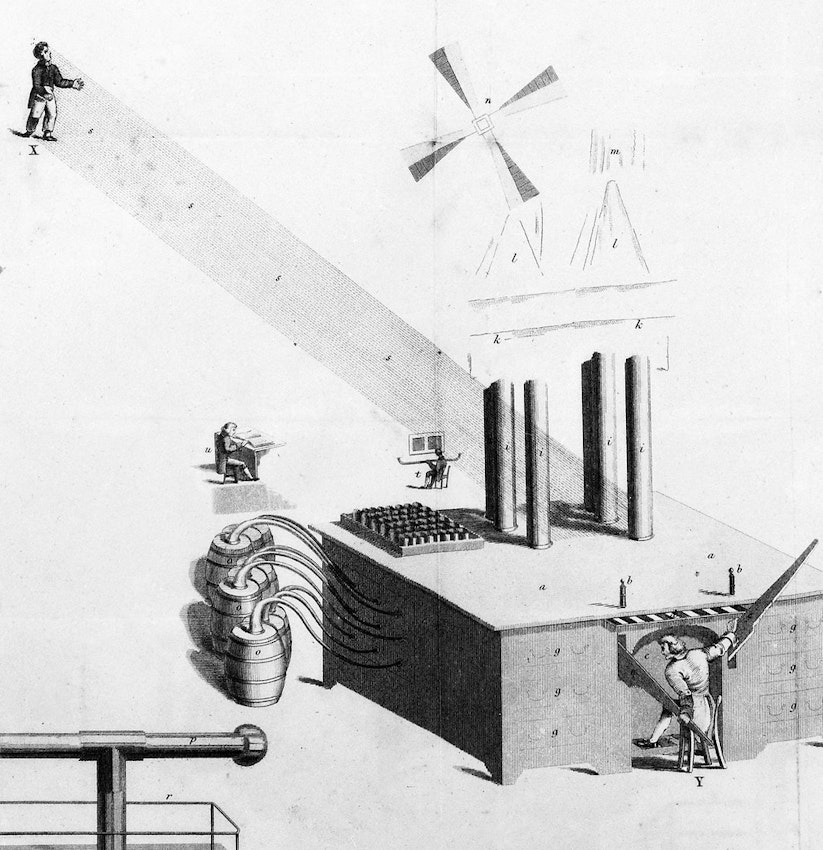

Over the ten years they had spent together in Bedlam, Matthews revealed his secret world to Haslam in exhaustive detail. Around the corner from Bedlam, in a dank basement cellar by London Wall, a gang of villains were controlling and tormenting him with a machine called an “Air Loom”. Matthews had even drawn a technical diagram of the device, which Haslam included in his book with a sarcastic commentary that invited the reader to laugh at its absurdity: a literal “illustration of madness”. But Matthews’ drawing has a more unnerving effect than Haslam allows. Levers, barrels, batteries, brass retorts and cylinders are rendered with the cool conviction of an engineer’s blueprint. It is the first ever published work of art by an asylum inmate, but it would hardly have looked out of place in the scientific journals or enyclopaedias of its day.

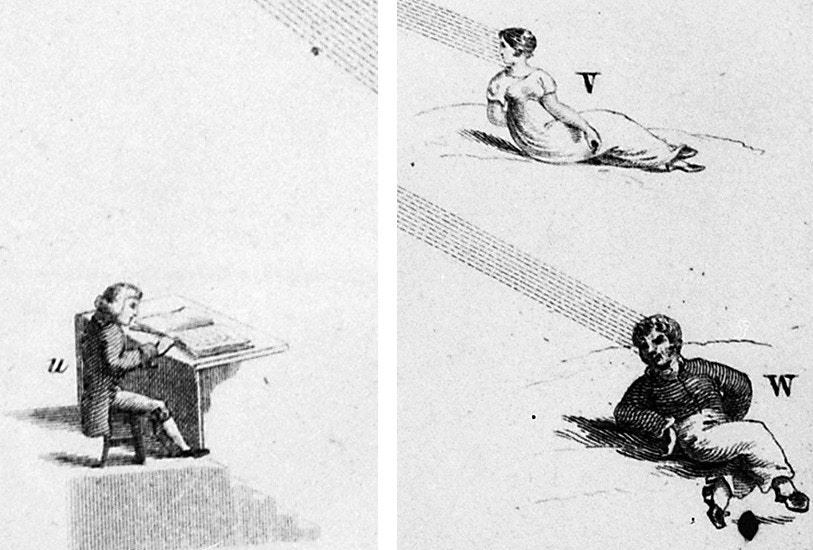

The Air Loom worked, as its name suggests, by weaving “airs”, or gases, into a “warp of magnetic fluid” which was then directed at its victim. Matthews’ explanation of its powers combined the cutting-edge technologies of pneumatic chemistry and the electric battery with the controversial science of animal magnetism, or mesmerism. The finer detail becomes increasingly strange. It was fuelled by combinations of “fetid effluvia”, including “spermatic-animal-seminal rays”, “putrid human breath”, and “gaz from the anus of the horse”, and its magnetic warp assailed Matthews’ brain in a catalogue of forms known as “event-workings”. These included “brain-saying” and “dream-working”, by which thoughts were forced into his brain against his will, and a terrifying array of physical tortures from “knee nailing”, “vital tearing” and “fibre ripping” to “apoplexy-working with the nutmeg grater” and the dreaded “lobster-cracking”, where the air around his chest was constricted until he was unable to breathe. To facilitate their control over him, the gang had implanted a magnet into his brain. He was tormented constantly by hallucinations, physical agonies, fits of laughter or being forced to parrot whatever words they chose to feed into his head. No wonder some people thought he was mad.

The machine’s operators were a gang of undercover Jacobin terrorists, who Matthews described with haunting precision. Their leader, Bill the King, was a coarse-faced and ruthless puppetmaster who “has never been known to smile”; his second-in-command, Jack the Schoolmaster, took careful notes on the Air Loom’s operations, pushing his wig back with his forefinger as he wrote. The operator was a sinister, pockmarked lady known only as the “Glove Woman”. The public face of the gang was a sharp-featured woman named Augusta, superficially charming but “exceedingly spiteful and malignant” when crossed, who roamed London’s west end as an undercover agent.

The operation directed at Matthews was only part of a larger story. There were more Air Looms and their gangs concealed across London, and their unseen influence extended all the way up to the Prime Minister, William Pitt, whose mind was firmly under their control. Their agents lurked in streets, theatres and coffee-houses, where they tricked the unsuspecting into inhaling magnetic fluids. If the gang were recognised in public, they would grasp magnetised batons that clouded the perception of anyone in the vicinity. The object of their intrigues was to poison the minds of politicians on both sides of the Channel, and thereby keep Britain and revolutionary France locked into their ruinous war.

Matthews’ beliefs had their roots in his implausible but true story. A political activist and peace campaigner, he had become involved during the French revolution in clandestine efforts to head off the looming war between France and England. Shuttling between London and Paris, he had remarkable success in persuading the moderate faction of the French government to commit to a peace plan, and he had met several times with Pitt and Lord Liverpool, his secretary of war, to propose an alliance with them against the Jacobins and the Paris mob.

But the execution of King Louis XVI in 1793 set Britain and France on an inexorable course to war, and Matthews was eventually arrested in Paris by the Committee of Public Safety on suspicion of being an English spy. He remained under arrest during the height of the Terror, in constant fear of the guillotine. When he was released three years later, he limped home to England and accused Pitt and Liverpool of abandoning a loyal patriot. His letters were ignored, and his accusations became more florid: Pitt’s government were secretly in league with the Jacobins, and prolonging the war for their own corrupt ends. Finally he confronted his betrayers in the public gallery of the House of Commons on 30 December 1796, loudly accusing Lord Liverpool of treason. He was arrested, judged to be of unsound mind and sent to Bedlam.

A view of Bethlehem Royal Hospital, London, from Lambeth Road, published in The Queen’s London (1896) – Source.

All Matthews’ convoluted tales of espionage and conspiracy were considered by Haslam merely as a symptom of his madness, and dealt with accordingly. His treatment of lunatics, as described in his earlier book Observations on Insanity (1798), stressed the need to “obtain an ascendancy” over the patient, a process comparable to training a dog or breaking in a horse. To debate with lunatics about their beliefs was to enter a “perplexity of metaphysical mazes”. Matthews in turn refused to acknowledge Haslam’s authority, maintaining that he was merely a stooge of the Home Secretary, yet another bit-player in the international conspiracy to silence him.

Confined and neglected, Matthews’ persecutory fantasies intensified. But his family refused to accept that he was mad. To them he still appeared his lucid, intelligent and gentle self: it was tragic but understandable that his traumatic experiences had left him with some cranky political views. Haslam’s theory of insanity, however, allowed for no such generosity. As he put it in Illustrations of Madness, “Madness being the opposite to reason and good sense, as light is to darkness, straight is to crooked &c., it appears wonderful that two opposite opinions could be entertained on the subject”. Matthews was mad: no-one who believed they were controlled by an Air Loom could be otherwise, and “there are already too many maniacs allowed to enjoy a dangerous liberty”. He banned Matthews’ wife from visiting him in Bethlem.

Portrait of John Haslam, engraved by Henry Dawe after a painting by George Dawe – Source.

Matthews’ family persisted with their case that he was sane, and offered to guarantee his good behaviour if he were released. Finally, in 1809, they were permitted to engage two physicians named Henry Clutterbuck and George Birkbeck to examine Matthews independently. Both concluded that he was in his right mind, and that his alleged symptoms of madness – hostility to authority and insistence that he was being conspired against – could equally be seen as the responses of a sane man unjustly confined.

On the basis of this testimony Matthews’ family served Bethlem with a writ of Habeas Corpus, forcing the governors to state their legal reasons for holding him. Haslam wrote a lengthy affidavit on Matthews’ case, detailing his delusions and claiming that he had made violent threats against the life of George III. In the end, however, the case turned on a short letter from the Home Secretary recommending “that you do continue to detain in your hosp[ital] as a fit and proper subject James Tilly Matthews a lunatic who is at present under your charge”. The Bethlem governors justified Matthews’ detention on the basis that he was “in the Hospital by the order and with the knowledge of Government”, and the writ of Habeas Corpus was rejected. Matthews, it seemed, was not a lunatic but a political prisoner, just as he had always maintained.

Having his medical opinion dismissed in this way spurred Haslam to publish a full account of the case. Illustrations of Madness opened with a withering attack on Clutterbuck and Birkbeck: “how they failed to detect his insanity is inexplicable”. He paraded Matthews’ delusions like a ringmaster in the circus of lunacy, advertising on the title page ‘a singular case of insanity, and a no less remarkable difference in medical opinion’, and tantalising the reader with the prospect of “a description of the tortures experienced by bomb-bursting, lobster-cracking and lengthening the brain”. All this was “embellished with a curious plate” – Matthews’ drawing of the Air Loom – and accompanied by excerpts from Matthews’ own notes on the “mischievous and complicated science” that lay behind it.

Title page to Haslam’s Illustrations of Madness (1810) – Source: Wellcome Library, London (CC-BY 4.0)

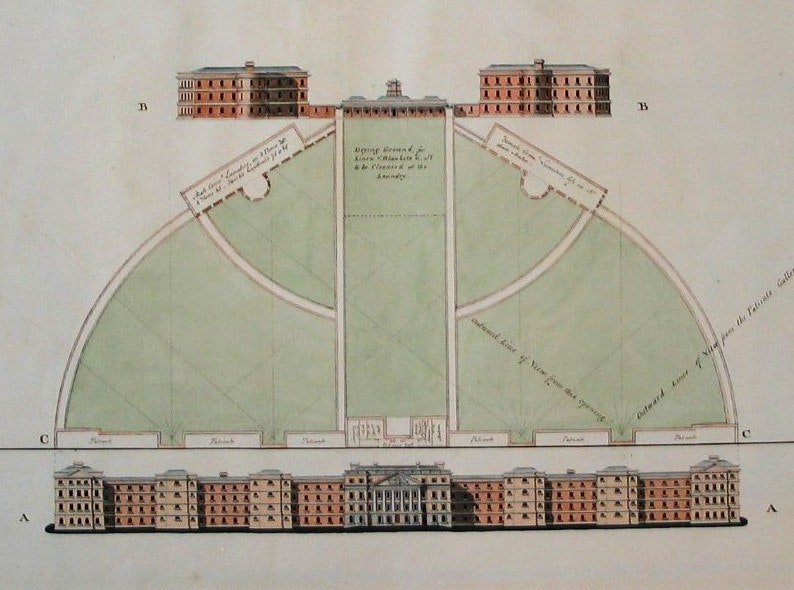

Although Illustrations of Madness was an extended argument for his permanent detention, Matthews managed to turn its publication to his advantage. His drawing of the Air Loom was admired by visiting doctors, and he began to teach himself draughtsmanship and engraving. The following year he submitted architectural plans for a new Bethlem hospital which so impressed the governors that they awarded him a prize of £30. In 1814 his family succeeded in transferring him to a more congenial private asylum, Fox’s London House in Hackney. Dr. Samuel Fox, the proprietor, regarded him as entirely sane, and he was soon helping out with book-keeping and gardening.

Matthews died the following year, but he had his revenge on Haslam from beyond the grave. In 1815 a House of Commons committee was set up to investigate conditions in madhouses, including allegations of mismanagement and cruelty at Bethlem. When examined, Haslam blamed the hospital staff: they were incompetent and frequently drunk, and the resident surgeon was “so insane as to have a strait-waistcoat”. In response, the head keeper testified that Haslam, frustrated by Matthews’ refusal to accept his authority, had kept him in handcuffs “to punish him for the use of his tongue”. Chaining non-violent patients had become emblematic of the evils of the old madhouse system, and indeed Haslam had criticised the practice in his own books. When the Committee’s report was published in 1816, he was dismissed by the Bethlem governors.

Haslam’s career was ruined. He sold everything he owned, doggedly retrained as a physician and eventually took his M.D. at the age of sixty. He became a specialist legal witness in trials involving criminal lunacy, giving his opinion on questions such as imbecility and “lucid intervals”. But Matthews’ case seems to have destroyed his certainty that the mad could be unfailingly distinguished from the sane. In his old age, when asked in court whether a defendant was of sound mind, he replied: “I never saw any human being who was of sound mind”. Pressed further by the judge, he simply added: “I presume the Deity is of sound mind, and He alone”.

Detail from one of Matthews’ plan for the new Bethlem hospital – Source: Bethlem, Museum of the Mind

By Mike Jay